In birds, fertilization is an action of… tightrope walkers: the female, after a suitable period of courtship, decides to stop by crouching on the ground, lets the male climb on her back, waddling in precarious balance until in an instant, having achieved the necessary coordination, the two bring their cloacal openings 1 into contact (cloacal kiss), and it’s all over. The female gets up, tidying up her slightly disheveled feathers, while the male moves away. Birds do not generally have a penis; only in some families, such as the Anatidae, does the male have two protrusions of the cloacal walls (pseudopenis) that, when protruded, facilitate the penetration of the sperm into the female’s cloacal cavity. A pseudopenis is found in the less evolved families of birds (tinamus, emus, cassowaries, kiwi) and overall in no more than 3% of known species.

However, if you see two pigeons on top of each other, it is not at all certain that the one on top is the male. Since the beginning of the last century, the phenomenon of “reverse mounting” or “female on male mounting” (hereinafter RM) has been described, an action that has generated more than one problem for those who deal with ethology and evolutionary biology, so much so that it is considered an evolutionary paradox. In fact, the context in which the RM behaviour is generated has not yet been defined and above all why it has not been eliminated by adaptive selection processes over time, given its certainly non-procreative purpose.

It was the laboratory studies of people like Julian Huxley and Charles O. Whitman, respectively on the Great Crested Grebe and the domestic pigeon, who first ascertained the phenomenon, then found so far in 42 species belonging to 11 of the 29 orders and 21 of the 249 families of birds. A number certainly underestimated to date, since in nature it is impossible to ascertain it for all the species in which male and female have the same color and pattern of plumage.

Looking at the species known to practice RM (from the Bearded Vulture to the Starling), we can deduce that they are monogamous birds, where both the male and the female participate in raising the offspring and in which RM occurs only in the reproductive period. In these, RM is a not rare phenomenon, amounting to 5-25% of the total observable mounts. Unfortunately, most of the observations of RM are only episodic, without going into the merit of the physiological, behavioural or cognitive stimuli that can induce it. We therefore have no idea of its proximate causes.

Very significant for me is the fact that in a species of North American woodpecker, the Carolina woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus), the RM is part of the stereotyped courtship sequence, while in another closely related woodpecker present in the same geographical area, the Red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus), the RM is not part of the courtship actions although it can be observed quite rarely in this period. Even in related species, the appearance of the RM may therefore have established itself in a completely different way. Furthermore, in the African hammerhead (Scopus umbretta), the RM appears opportunistically even outside the pair bond, but always during the reproductive period.

A proximate cause of RM could however also be pleasure. Such a cause may encounter difficulties in being admitted depending on preconceived positions on the quality and degree of interpersonal relationships that occur within a species. This is taking into account that studies on the subjective state of animals and on their disposition towards non-procreative sexual behaviors are not common, so we know very little about them. Despite this, there is a growing consensus in admitting that pleasure derived from sex is present in non-human species, including birds. This would make it a causal factor of RM also for the latter.

In such a state of uncertainty, several hypotheses have been proposed over time to explain the evolutionary origins of RM, which I summarize in Table I.

Table I. Hypotheses on the evolutionary causes of Reverse Mounting (RM) in birds

1 – Aberrant Behaviour: RM appears randomly and is not part of the sexual repertoire of the species.

2 – Inseminative Hypothesis: RM leads to the insemination of the female.

3 – Ovarian Stimulation Hypothesis: RM stimulates the maturation of ovarian follicles, increasing fertility.

4 – Super-normal Sexual Stimulation Hypothesis: RM acts as a super-normal sexual stimulation, inducing copulation even in males who are momentarily disinterested in it.

5 – Aggressive Hypothesis: RM appears in an aggressive context or in any case in which dominance is affirmed.

6 – Social Cohesion Hypothesis: RM strengthens social cohesion within a group.

The first hypothesis is clearly non-adaptive, as it considers RM an aberrant behavior typical of some females, without being part of the sexual repertoire of the species in which it has been observed. Historically, it is the first hypothesis expressed but today it is considered completely unsatisfactory given the recurrent presence of RM in so many species. If this has established itself and maintained itself, there must be “a fortiori” evolutionary adaptations that have allowed its survival.

The other five hypotheses are all adaptive and often not exclusive but interacting. In them, RM could directly influence reproductive fitness 2 (2,3,4), or increase it indirectly through a modulation of the social behavior of the species (5,6).

Hypothesis 2 of the persistence of insemination in RM has been postulated only for our Common Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), a common guest of humid areas, but very recent observations on other species have shown that such a hypothesis is not sustainable for them. Hence the very little credit that derives from it at the level of the real possibility of its evolution for the possibility of insemination.

The stimulation of ovarian follicle maturation (hypothesis 3), instead, is seen as one of the possible drivers of the evolutionary affirmation of RM, especially if temporally followed by regular mounts, as actually happens in many species.

For hypothesis 4, RM would work for the male as a super stimulus from the female, inducing him to increase his interest in the partner especially in the initial and final moments of the breeding season. In this way, a greater number of layings would be obtained, with a possible increase in the reproductive fitness of the pair. Furthermore, in the initial moments of the breeding season, RM would contribute to the stabilization and strengthening of the pair bond. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that RM are more frequent in the initial and final moments of the breeding season, rather than in its central moment.

Hypotheses 5 and 6 are directly linked to the socio-sexual dynamics of different species, modulating the behavior of male and female towards the construction of a pair bond. Especially 5 could have a strong role in reducing the aggressive dominance of the male towards the female, inducing a more balanced role within the couple. In several species, the male’s aggressiveness can even cause physical damage to the female with a non-negligible reflection on the reproductive fitness of the future couple.

Regarding 6, in highly social species, RM may strengthen cohesion between group members. The hypothesis has been advanced for species in which RM is commonly visible outside the pair bond but between group members, as in the Hammerhead and the European Shag (Gulosus aristotelis).

But then what?

It is better then to admit our inability to correctly interpret the phenomenon. Giving it an explanation that satisfies its evolution and maintenance in many species (which could become many more with the progress of observations) is not possible at the moment. There are no studies that attempt to explain from a comparative point of view how it could have established itself in the innate reproductive repertoire of different species of birds, a fact that causes a significant research gap.

Certainly, RM must be evaluated within the phenomena of sexual selection, that is, the interactions between individuals of the same species that influence their reproductive success. The manifestation of RM in a species is obviously innate and does not represent an episodic or aberrant fact; it must therefore have a measurable and significant influence on sexual selection.

RM has been known to ornithologists since the dawn of the last century but no one has addressed its evolutionary problem. It will be the task of evolutionary biology to search for the ways of selective affirmation through comparative ethological studies, so that in the future the hypotheses put forward here assume an actual meaning or are completely revised.

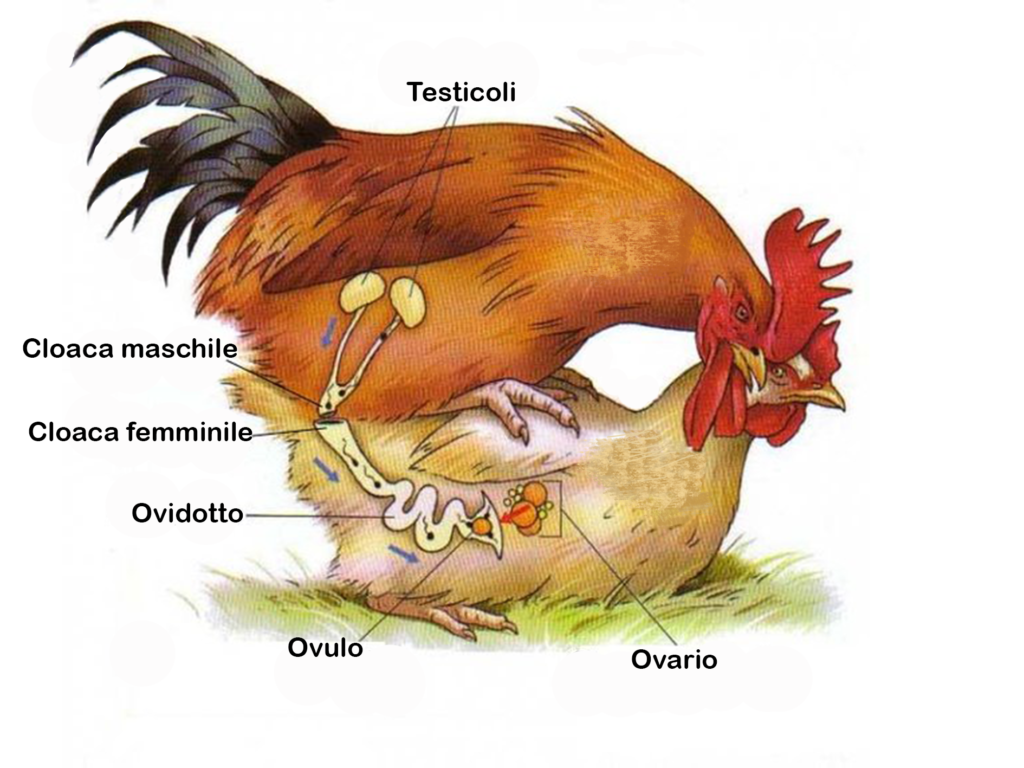

- Aperture cloacali – Negli uccelli sono cavità nella quale sboccano i condotti dell’apparato digerente, dell’apparato genitale e dell’apparato urinario. ↩︎

- Fitness riproduttiva – numero di discendenti procreati. ↩︎

This contribution was inspired by the work of Daniel Villar (Oxford University, UK) entitled “Reverse Mounting in birds” recently published in the scientific journal “Ethology Ecology Evolution”.

Credits

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic resources at University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers on national and international journals. He is active in the field of scientific education, and co-author of academic textbooks of Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, Comparative Anatomy.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa