The three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) is a small fish made particularly famous by the studies that Niko Tinbergen carried out on it, so much so that it is considered a true icon of the behavioral sciences. Certainly, on the same level of Konrad Lorenz’s geese and Karl von Frisch’s bees, the two scholars who in 1973 earned the Nobel Prize with Tinbergen for their ethological research. By studying his social behavior, Tinbergen clarified fundamental aspects of ethology, such as the existence of so-called “key” stimuli, capable of inducing certain instinctive actions in the individual of the reproductive, competitive and territorial systems. On the behavior of the Three-spined stickleback he also based one of the two hypotheses existing today of temporal and hierarchical organization of animal behavior.

But what is this little and famous fish like?

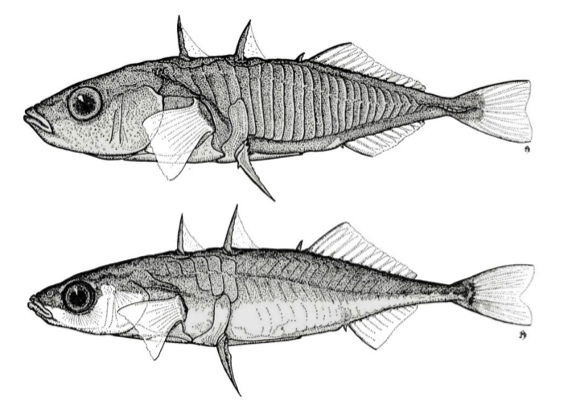

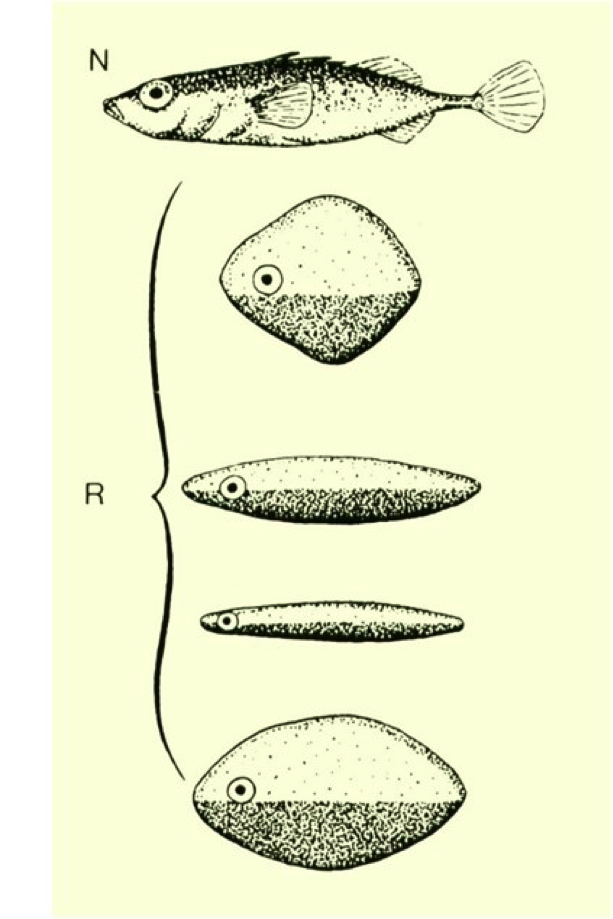

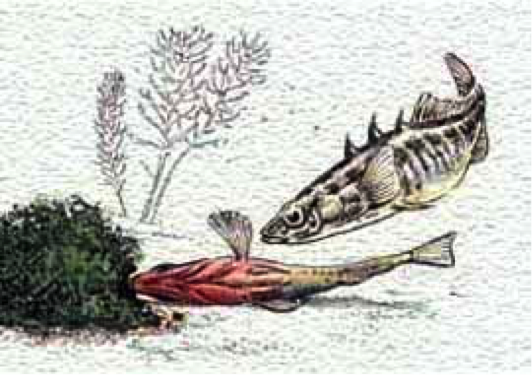

The Three-spined stickleback owes its Italian name to the showy bone spines it has on its back and belly, as can be clearly seen in the figure.

Below: the leiurus form, in which the dermal plates are much less present.

It rarely exceeds eight to ten centimeters and its body is more or less covered with dermal bone plates variously developed in different populations. The anti-predatory function of the spines appears obvious but certainly is not sufficient to ensure the small fish safe protection from predatory fish such as trout or pike and even less from the aerial attacks of the kingfisher. Of the three-spined Stickleback, which has a very wide distribution in European and North American rivers, two distinct forms are known. The first has migratory habits: it lives in coastal marine waters and goes back to those rivers and lagoons only for reproduction. The two forms are inter-fertile and generate specimens with an intermediate plate complex, as occurs in the contact areas between the two different populations. The Italian population belongs to the second form with lighter armour, with three spines in front of the dorsal fin which have grown with as many dermal plates. A small spine also precedes the anal fin, while on the right and left the first ray of the ventral fins is transformed into a further spiny bone ray. Hence the Anglo-Saxon name of “Three-thorned stickleback”, differentiates it from two “cousins” not present in our fauna, which have a dozen or so backbones (10-spined three-spined stickleback).

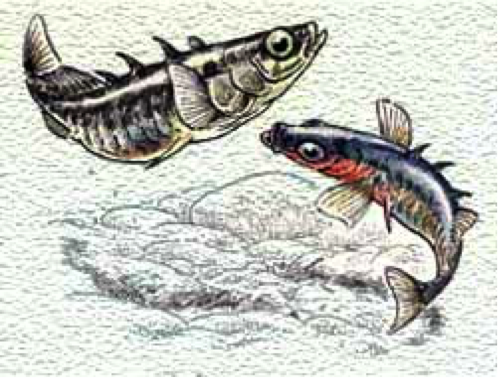

If these morphological peculiarities are only the joy of taxonomists and systematists, the reproductive behaviour of the Three-spined sticklebackhas long interested ethologists, who have drawn entire chapters of this scientific discipline from it. During the non-reproductive season, males and females gather in small groups, not disdaining each other’s company. As spring approaches, winter gregariousness vanishes to give way to a decisive territorial behavior of males, who isolate themselves by establishing their own territory, unlike females who remain in non-territorial groups. The hormonal storm triggered by the maturation of the male gonads causes a change in the color of the belly of males which, due to the action of chromatophores loaded with red pigments, becomes a vivid cherry color. Even the eyes become a bright blue, while the back takes on a greenish color instead of a greyish hue.

Photo by Pulmarüüs isane ogalik

The colouring is under hormonal control and will remain unchanged throughout the reproductive period. The females, on the other hand, maintain their usual pale greenish-gray color, with a hint of transverse bands, common to all members of the species. However, their silhouette changes as the ovary produces mature eggs, so much so that their belly swells in a very decisive way, clearly visible both in the side profile and from above. The female “swollen belly” thus constitutes for the male a clear signal of sexual maturity and therefore of disposition to lay eggs. The territory, no more than a few square decimetres wide, is established by the male at the bottom of the waterways, in areas rich in aquatic plants, and is fiercely defended, chasing away possible competing males. A mature male never abandons it, rushing towards any intruders, exhibiting his reddish belly and assuming a typical vertical upside-down position in front of them.

Normally these two visual cues (red belly and head down) are sufficient to discourage rivals, in a typically ritualized and non-bloody aggressive context. You can rarely switch to action with short but quick chases, hitting the hips less ready to react to the threat signals “place occupied, dislodge”! In any case, in aggressive contexts, the owner of the territory is constantly the winner, a fact that appears to be common to all the competitive episodes that take place in occupied territory.

The ability of the red coloring of the belly to constitute a clear and unequivocal signal was discovered by Tinbergen with experiments in which a territorial Stickleback was shown a perfectly made wax model but without the red belly, and others completely coarse but with the lower red.

The dark part at the bottom of the models was colored red.

The first model (see the previous figure) did not arouse any competitive reaction, unlike the others that were persistently attacked as long as they were not removed from the aquarium. A curious but interesting anecdote about the power of the red signal was once told by Tinbergen: some aquariums with Sticklebacks in the territorial phase had been accidentally placed in front of a window overlooking the street. Altogether they were agitated for no apparent reason and at about the same time, bumping against the glass from the outside. He unveiled the mystery when he realized that the agitation was induced by the passage of the postal van, in Holland, which was red in color, which they mistook for an opponent!

The Stickleback has a precise visual knowledge of the boundaries and the structure of its territory, acquired through the memorization of salient elements such as stones, aquatic plants, and the like. We can therefore speak of a “cognitive map” of its territory, which the animal must insert into a neural network in order to be able to memorize it stably. When a Stickleback attacks an intruder, it threatens and chases him to the limit of his territory, no further; there he stops, satisfied with what he has done.

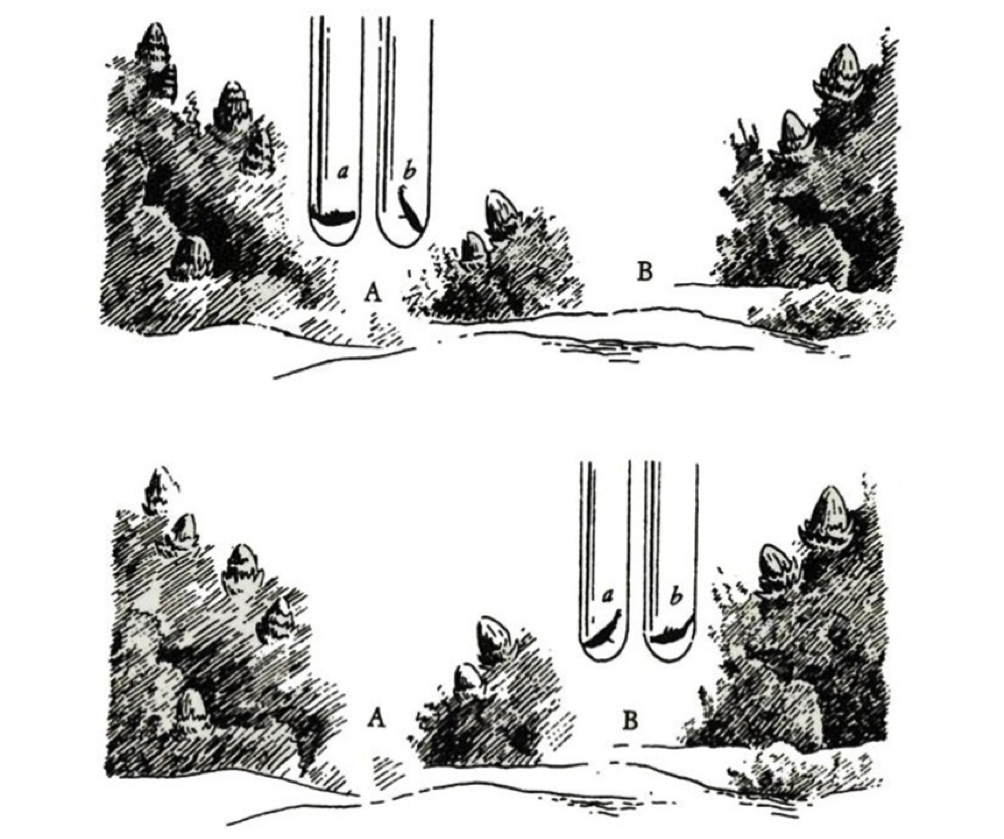

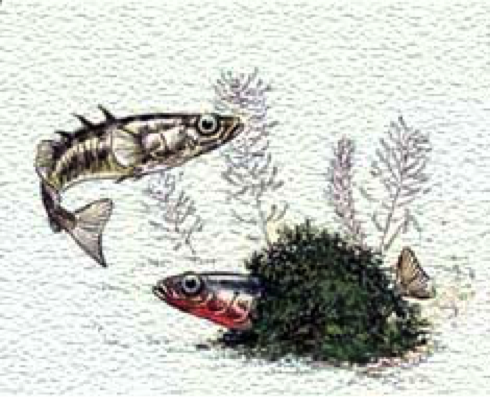

Illuminating was the Tinbergen experiment in which, in a sufficiently large aquarium, two Sticklebacks established their distinct territories. Captured and placed each in a large glass test tube, Ciccio and Lillo (let’s call them that) were placed together in one or the other territory (next image). In Ciccio’s it was he who was trying to attack Lillo, banging furiously against the glass while the other tried in vain to escape in the opposite direction. Just the opposite happened when the two test tubes were moved to Lillo’s territory: he attacked, and Ciccio fled. They were therefore able to readily recognize where they were and behave accordingly. The reproductive status and motivations were the same, but what mattered was where they were.

For the Stickleback, the territory is above all a reproductive area, which is why it ardently defends it. It is in fact there that he builds the nest, it is there that he attracts the females and he will raise the young in solitude with appropriate and solicitous parental care. All with a wealth of instinctive actions, the result of the evolution of motor programs typical of the species and genetically transmitted. It has been proven that Sticklebacks raised in isolation from the egg stage will be able to exhibit those same instinctual actions at the time of reproduction.

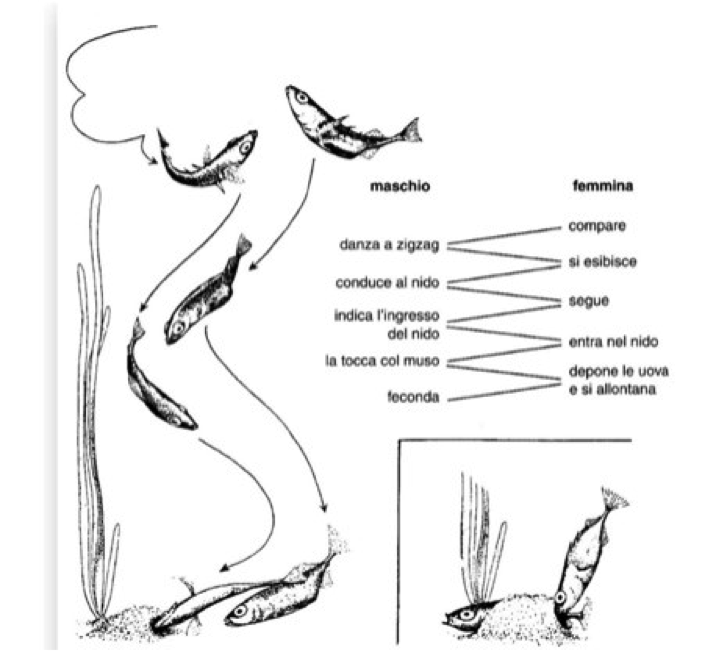

In a position as central as possible with respect to the borders of the territory, the male builds him nest, collecting and cementing together with a renal secretion, a ball of algal and herbaceous filaments, no larger than its own length. With blows of the muzzle, he pierces it, giving it the shape of a sleeve, anchored to the stony bottom or to marsh plants. Reproduction is polygamous, as the same male attracts several females in succession to the nest, inducing them to unload their eggs. This happens with a chain of courtship actions closely coordinated with the female, in what Tinbergen called a “zig-zag dance”, represented in the following figure, as he portrayed her: a figure that we can find today on the cover of many texts of Ethology for its historical relevance.

When a mature female approaches his territory, the male quickly goes towards her with a zigzag swim, attracted by her swollen belly. She exhibits it with an upward arching movement as she approaches, a key stimulating signal that indicates her willingness to reproduce.

The movements toward her are followed by equally rapid jerks toward the nest. The ascents and descents are repeated several times, until, having reached the necessary coordination, the female follows him and is invited to enter the sleeve-like nest by the male, who, turning on his side, slips his muzzle into it.

The female then tries, writhing, to enter it and, after several attempts, finally manages to do so with an energetic flick of the tail, letting the muzzle and the tail stick out.

Once inside, the male stimulates her to lay with short and repeated taps at the base of the tail, until she, by raising it, discharges the eggs, at least a hundred, no larger than two millimeters.

At that point the idyll is over: the female disappears quickly, and the male enters the tunnel and sprinkles the eggs with sperm, fertilizing them. Left free, he will be able to court other females, usually three or four, completing the multiple broods.

The nest full of eggs is the signal that pushes the male to start parental care, stopping to run towards the females with “swollen bellies” and behaving like a good family man. Certainly, he must try to keep away possible egg predators, including congeners who certainly do not shy away from a substantial meal. His main problem, from now on, will be to ensure sufficient ventilation for the eggs, providing a continuous passage of water in the sleeve nest: he does so with a persistent flapping of the pectoral fins in front of the access hole, remaining in a precarious balance of position with movements of the tail. In the seven to eight days of hatching, this will be an ever-increasing task, passing from a few minutes an hour to the beginning of the development of the fry, until at the end of the week the ventilation takes up three-quarters of the day. This increase is due to a growing internal motivational impulse to ventilate, certainly functional to ensure a parallel increase in oxygenation to the brood.

When the fry begin to move around, now without the ventral yolk sac, the male stops ventilating and goes to supervise the copious and restless group of small fish, trying as much as he can to keep them united within the territory. More and more lively, they need to rise to the surface to swallow an air bubble, functional to the proper development and functioning of their swim bladder. The thing is not easy and they have to do it quickly, because the father does not tolerate escapes and, for this reason, he chases them by taking them in the mouth to spit them back into the group of brothers. During the two weeks following leaving the nest, the battle becomes uneven even for the most apprehensive father. The little fish swarm in small groups and he loses all interest in defending them. His colors gradually fade, the skirmishes between neighbors cease, and the taste for gregariousness with congeners males and females is resumed, satisfied with the efforts of territorialism and reproduction. It is time for a drastic change in the social system: they are preparing for the bad season, migratory populations will soon return to the sea, and the settled ones will form small groups in the waters of streams and springs. An annual cycle has ended, and there will be time for hostilities in the following spring.

Credits:

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic resources at University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers on national and international journals. He is active in the field of scientific education, and co-author of academic textbooks of Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, Comparative Anatomy.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa