The oblique rays of the sun that light up the clear winter days illuminate the innermost and deepest parts of the bushes, shrubs and treetops, highlighting the colours of their berries. Red, purple, blue, black, brown. It is their bright colours that are the first attraction for insects, birds and mammals that will help plants disperse their seeds.

Producing fleshy fruits is one of the reproduction strategies of many plant species that entrust animals with the task of carrying their seeds where their branches cannot go. To “convince” the animals to help them achieve this goal, they offer them the sweet, and therefore very energetic, pulp of their fruits.

(From ”Le stagioni del bosco” by A. Lacci and R. Savio. San Marco Litotipo, Lucca 1996).

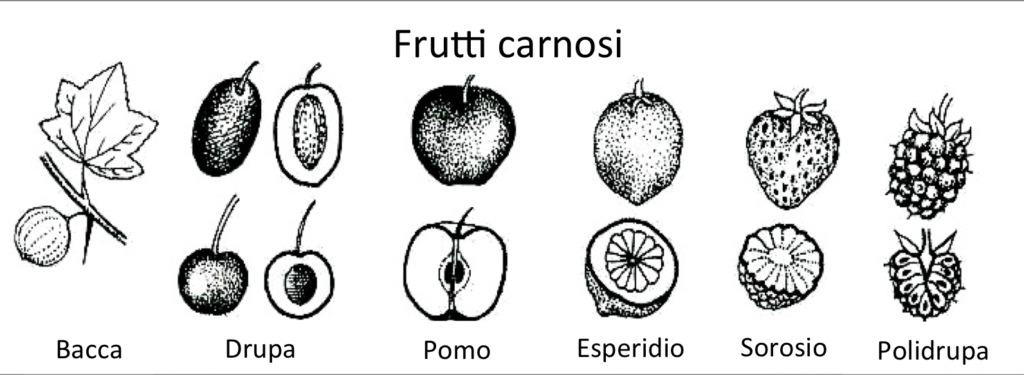

The berries are part of those fleshy fruits produced by many plants belonging to the angiosperms, flowering plants that are the most evolved and best-known group of plants. The word “angiosperm” comes from the union of the Greek word aengeion = envelope and from the Latin sperma = seed; therefore “plant with seed in an envelope” in our case the seed is enclosed and protected inside the fruit.

The berry derives from the transformation of the ovary of the flower and the seeds, deriving from the transformation of the ovules, are immersed in the pulp. When a bird or mammal feeds on a sweet, colourful berry, it swallows the seeds. These survive digestion and are then released into the environment upon defecation. In some cases, digestive enzymes trigger the germination of seeds in the soil. Both organisms, therefore, benefit from this mode of interaction: the animal feeds itself, and the plant propagates.

(For more information on this species see https://www.earthgardeners.it/2018/05/07/biancospino-comune/)

Generally, a fruit that looks like a berry but actually isn’t is often referred to as a berry. In the case of the Rosaceae, for example, both the Hawthorn and the Rosa genus have fruits that look like berries but the former is a drupe and the latter are rose hips.

Berries and other small winter fruits are of great ecological importance because they represent an important source of energy, both for sedentary and wintering birds and for mammals that do not hibernate.

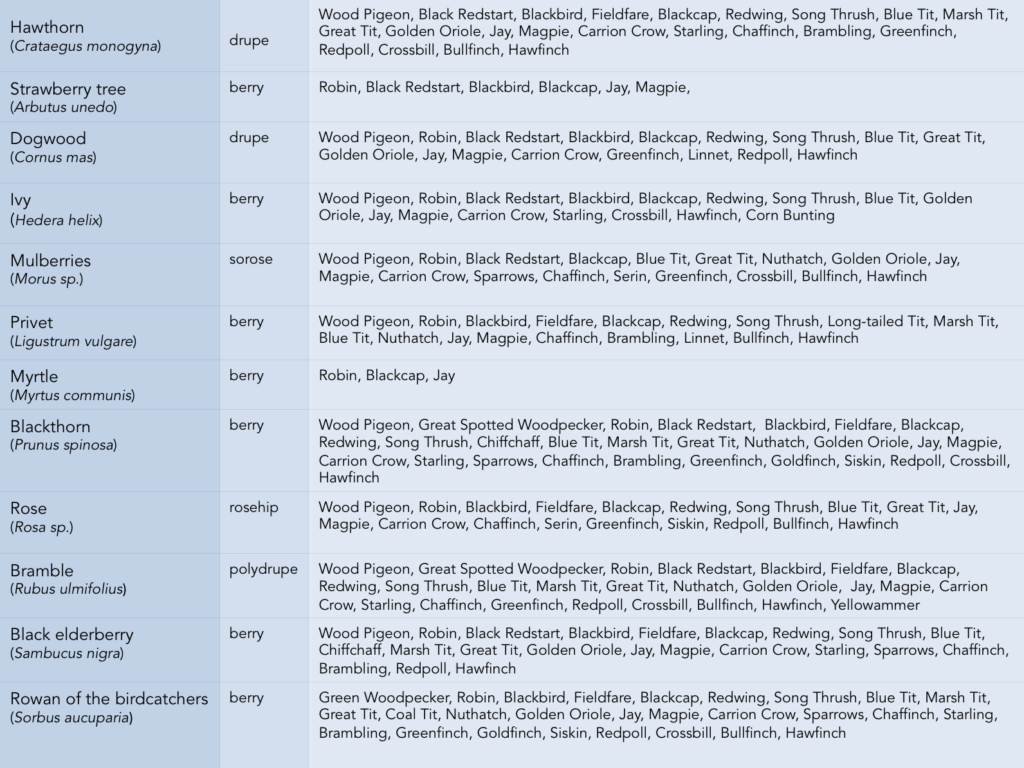

The following table includes some of the most widespread and known species of the Mediterranean flora; if you read it carefully you will see how there are birds that draw on the fruits of several plant species and others which prefer the fruits of very few shrubs or trees.

If, for example, hedges and, consequently, Blackthorns or Elderberries are missing in an agricultural environment, the presence of the Chiffchaff, is decidedly difficult. We note, however, how the great, sometimes excessive, diffusion of Crows, Wood pigeons, Starlings and Titmice depends on the great variety of their diet.

From these observations we can easily understand that if an ecosystem can count on the presence of many plant species that produce “fruit”, a greater presence of faunal species is induced, i.e. faunal biodiversity largely depends on flora biodiversity. It is also evident how adaptability to different environments is the most important characteristic for diffusion and therefore for the survival of a species.

The fleshy fruits that trees and shrubs make available to the fauna during the winter are not only appreciated by frugivores or herbivores in general, but also by insectivorous birds and mammals with a mainly carnivorous diet.

Photo by Der Weg.

The birds which feed exclusively on insects in spring and summer because the rearing of their offspring requires a large supply of proteins, during autumn and winter, seasons in which insects are difficult to find, change their diet and feed on fruits that still give them the energy to overcome the rigors of winter.

Deer, roe deer, fallow deer and mouflon find in the berries a valid caloric contribution to a diet essentially made up of leaves and bark.

Unlike the Stone marten which, by catching its victims mainly while they are sleeping, has an essentially carnivorous diet in winter, the Fox enriches its omnivorous diet with berries and small fruits to make up for the difficulty of finding reptiles and small rodents, which in winter are in the den for hibernation or for shelter from bad weather.

When the ground is covered with snow, while the Boar, in addition to feeding on the fallen fruit, manages to dig with its snout to reach the roots, the Hare has to be satisfied with the fruits “at its height” while trying to avoid becoming itself food for other animals.

And so, from berry to berry, step by step, wearing gloves and a scarf, on a cold February morning, you can discover the interweaving that binds the species, the environments, and the destinies of those who live on the Blue Planet.

Credits

Authors:

Anna Lacci is a scientific popularizer and expert in environmental education and sustainability and in territory teaching. She is the author of documentaries and naturalistic books, notebooks and interdisciplinary teaching aids, and multimedia information materials.

Lina Podda. A naturalist, she is involved in research in the field of alien plants and cultivates a passion for marine biology by collaborating with the CEAS Marine Protected Area of Capo Carbonara.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa