One of the central points of the ecological transition is certainly that of the progressive abandonment of non-renewable energy sources, favouring instead the use of renewable ones.

Hammers and millstones moved by flowing water or by the wind as well as the production of electricity through dynamos activated by water conveyed in penstocks are virtuous examples of green technology. However, these, which were sufficient to satisfy the energy demands of the distant past, are now only marginally so in the current context of a civilization that is fortunately increasingly aware and aware of the limits that will be imposed on it in the energy field and the consequent scenarios.

Taking advantage of the virtuous technologies of the past, at least in limited environmental contexts and considering how problematic and economically prohibitive the uses and supplies of fossil energy sources have become, all that remains is an absolute openness towards renewable ones.

These, in the context of careful use, can help us maintain lifestyles that are now acquired, but increasingly burdensome for the health of our planet. A general rethinking in terms of energy is now unavoidable, in the awareness that a change of approach is necessary immediately.

The current trend towards renewable sources of energy passes through wind power and photovoltaics in a decisive way, although they too are not free from environmental problems that have limited their faster and more effective development. If photovoltaic on a domestic scale today boasts a wide and economically very advantageous application, wind power has always posed environmental problems of a landscape nature but also of direct impact on fauna.

The landscape problems are undeniable; they were particularly so in a phase of “wild” construction of plants which involved some of our regions. Rows of turbines over mountain ridges which were continuously stricken by wind, ended by violating pristine pastoral landscapes. But certainly, as an old adage recalls, “you don’t light a lamp to put it under a bushel” (Italian: “non si accende una lampada per metterla sotto al moggio”) and if wind power was to be generated, those were the places to operate efficiently.

Putting up a wind turbine has never been an administratively simple procedure, far from it. The bureaucratic process is asphyxiating, but so was the political attitude and often the unpreparedness of the administrations. How many regional governments are there who, from the top of their full and exclusive responsibility, have prepared preventive plans in time to facilitate the development of wind power, and how many instead have closed their doors a priori? And then wind power yes, but at other people’s homes!

Even preventive planning of the places and of the necessary bureaucratic procedures has in some cases had both a facilitating and an impeding purpose to the realization of wind farms, with virtuous regions aware of their importance and others that erected insurmountable walls.

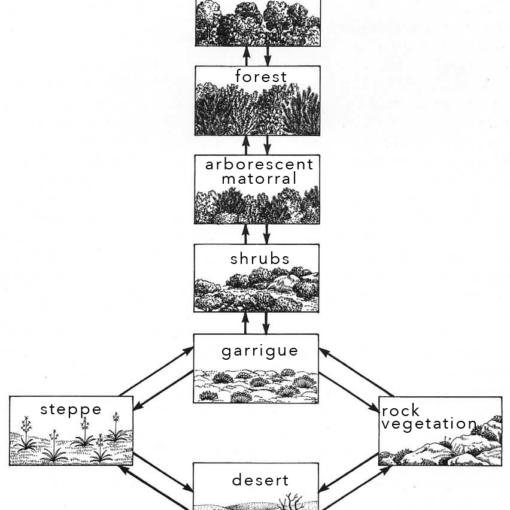

Effective planning is certainly not easy to do, requiring the crossing of data of various kinds, both meteorological (areas with constant winds), environmental (flora and fauna), landscape, location of protected areas or areas of Community interest… with the aim of cartographically identifying areas suitable for the effective positioning of the shovels, without clashing with the purposes of integrity and protection of the places and flora and fauna populations that insist thereon.

Once the areas for possible planting have been identified, the road to planning should be easy, with the certainty of a bureaucratic process that does not require the doubling of already known environmental analyzes or faunal investigations that are impossible to carry out even by accredited research institutes, as unfortunately often happened.

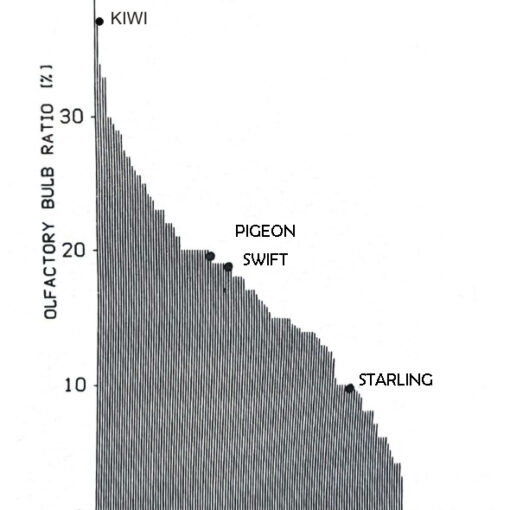

The possibility of a direct impact on bird fauna is a factor that has certainly held back the development of wind power. Assuming that there have been forcings in this sense, this event cannot be excluded a priori. But what is the objective scope of the phenomenon, and what are the possible remedies?

In the extensive wind farms in southern Spain, researchers have actually identified “killer” blades, so named because they are capable of causing lethal impacts for birds. Once recognized as such, they were simply deactivated. Equally, in fields located on important migration lines (which effective planning must avoid!), the installation of bird radars that deactivate the blades during migration peaks has solved the problem brilliantly.

Speaking of the turbine/bird relationship, however, I cannot forget a sight that is hard to forget: towards Capo Corso, where the wind turbines are teeming, a vulture was playing (this is my impression) with a turbine. Exploiting the vortex it generated, the bird let itself be dragged upwards, fell back and again climbed along the edge of the blade itself… it moved away and returned to start again, a mesmerizing thing.

I myself blocked the construction of a wind farm on the edge of a regional park, where two pairs of lesser harrier had been nesting for some time in the immediate vicinity and a rare population of purple heron crossed the line of planned generators during foraging flights. The same fate for another projected field on the beautiful Apennine peaks: it is a pity that those reliefs were ophiolite islands on which endemics and flora typical of those lands insisted, which would have been completely lost during the construction works. Only a team of ecological specialists could have the competences and the courage to stop this regional planning.

What must be firmly requested is not the stop (emotional in many cases) to the construction of a wind farm, but the need for correct and reliable environmental assessments, subject to qualified scrutiny in special and open Service Conferences. All this with the full picture in mind. I was really surprised when I verified the large number of wind turbines that exist in the Rhone delta, i.e. in the Camargue, one of the most famous ornithological places, the gateway for millions of migratory birds which, having left the Mediterranean, head towards central Europe along the valley of that river. Lastly, I would like to cite the example of maritime lighthouses: at their base, many birds gather and slam into them during migratory nights. Those lighthouses are necessary, no one ever wanted to turn them off.

We need green energy, let’s not extinguish it with prejudices

Credits

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic resources at University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers on national and international journals. He is active in the field of scientific education, and co-author of academic textbooks of Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, Comparative Anatomy.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa