Birds are the masters of the air and their spatial navigation capabilities are well known. No less so are some marine organisms, such as turtles, tuna, eels or whales capable of migrating across the oceans, following routes that extend for thousands of miles. Recent research done with Federica Maffezzoli and Augusto Foà, has however highlighted that even the small lizards of our fields (Podarcis siculus) are able to return home when taken to places unknown to them, since they know how to orient themselves towards the destination directly after release. This means that they too possess navigation mechanisms like other much more celebrated animals. The distances in play this time are tens or hundreds of meters, but considering their size, such a result was certainly not a foregone conclusion.

It has been known for a long time that some lizards (Lacertidae, Anoles, Skinks) were able to return to the place of capture. However, no one had ever recorded their escape directions after release. It was therefore not known whether and how the return home was based on a casual search or the result of an effective orientation mechanism towards it. This is the original element of our work.

Lizards are lively animals, capable of very rapid movements and endowed with excellent eyesight. Males and breeding females are tied to a familiar area (home range), i.e. where their den is, and where they know how to move confidently from one point to another. Inside it, the males also defend a portion with actual territorial value. Even more interesting is the fact that the field lizard is able to use the sun as a compass, as demonstrated experimentally by Augusto.

The first step in the research was then to establish the actual size of the territory and the familiar area of the country lizard, beyond the completely erroneous data present in the only known work on the subject, as we soon realized. This information was essential to be able to take the lizards to a place that was not known to them in the experimental tests.

To conduct the research, we chose a large clearing of about 9 hectares in the Tenuta di San Rossore (Pisa), homogeneously surrounded by pine and holm oak woods, with a large presence of lizards located especially near ruined buildings, walls or piles of wood. Here, both the observations on the familiar area and, subsequently, the orientation experiments were carried out; indeed, many of the lizards followed by sight for days in their movements were then used for the latter.

The country lizard is almost always characterized by two green stripes that run along the animal’s back. It feeds almost exclusively on insects and prefers open and sunny places.

Males and females (not pregnant) under observation had been captured in their den, marked on their backs with a personal sequence of non-toxic colors and immediately released. From there they were taken care of by willing and passionate students led by Federica, who had been observing lizards along the sunny paths of the Mantua countryside for a lifetime and who would draw her degree thesis in Biology from these experiments.

The results of these observations allowed us to estimate the size of the family area of the males at an average of 217 m² and that of the females at 156 m² (all adult specimens no less than 5 cm long, tail excluded). The shape of the family area could be nucleated or more or less elongated but it was clear that the individuals remained at a distance of no more than twenty meters from the den. Taking them further away therefore meant lowering them into places foreign to them.

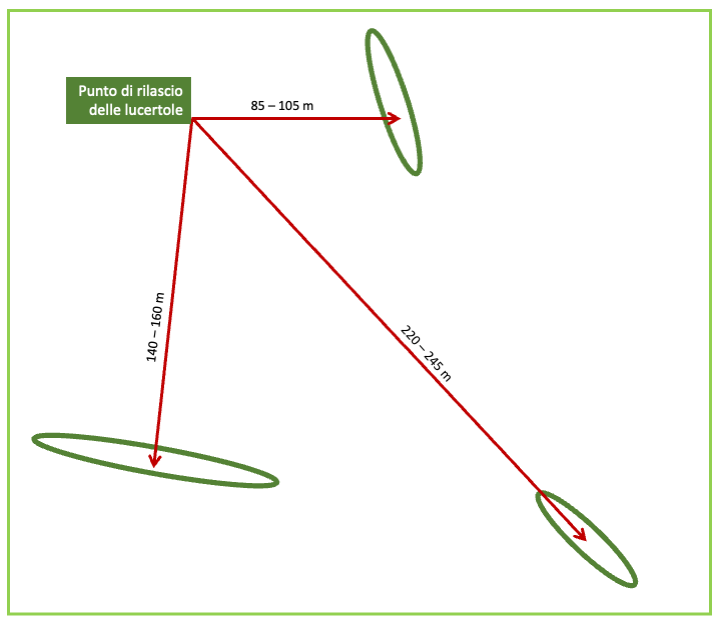

Once the first step was taken, we organized the dislocation and release tests based on our experience in homing experiments on birds: we captured the lizards, marked them and transported them to a common release point, then released them individually, noting the direction of escape taken and the time of any re-sighting in the home area. The areas of origin of the lizards were respectively: 85-105 meters; 140-160 m; 220-245 m from the release site and included an approximately equal number of males and females. The transport took place on foot along paths with various changes of direction, in plexiglass and net cages. For some, the cages were uncovered, for others protected by a cardboard cone that did not allow a view of the landscape. At the release point there was a small wooden platform, from which the lizards were released, following them by sight until they passed a circle of 15 meters radius traced on the ground around: that was the point that, detected with a compass, indicated the direction of escape of the animal. Having detected at the moment of capture of each lizard, the direction of the release point from its den, it was thus possible to calculate the precision of its orientation with respect to the site of origin. In total 74 lizards were released (42 males and 32 females).

The results obtained can be summarized in the following points:

- All groups of lizards (males + females) released from the three distance bands showed a significant average orientation towards their home direction;

- this was true both for groups of individuals transported without the view of the landscape towards the release site and for those who could see it;

- considering separately the orientation of males and females, both resulted oriented on average towards home;

- the conditions of transport did not affect the quality of the orientation;

- males and females showed the same orientation qualities;

- all 74 lizards tested returned to their familiar areas, demonstrating complete homing success: 11 did so on the same day of release, 51 the following day, 12 two days later;

- also in this last case males and females returned home at no different times.

We were the first to greet with surprise these results, which, if they confirmed some preliminary observations made to better prepare the methodological protocols, left no more doubts about the orientation and navigation potential of this species of lizard, rightly protected by the Community “Habitat” 1.

From a more general point of view, our results open up several contexts of certain interest. The fact that males and females have a spatially defined family area, which for males also includes a smaller territorial area, strenuously defended by conspecifics with great energy expenditure, determines in both a strong motivation to return there, fully justifying the homing success as well as the rapid return of the tested individuals. The difference in the extension of this area between the sexes is not sufficient to induce behavioral dichotomies detectable at this level: males and females demonstrate comparable return performances.

Being able to measure the initial orientation of the displaced individuals certainly represents the greatest result obtained, demonstrating that after a few minutes from the release, the lizards exiting the 15-meter circle had already had the possibility of identifying their destination. This even though they had not been able to see the landscape during the transport and the latter had occurred with many changes of direction.

Such orientation and homing behavior can only be ascribed to a “true navigation” mechanism. For a lizard, this mechanism can be based on the memorization of compass directions of salient elements of the landscape in which it lives, which would constitute a cognitive map of the landscape itself. That is to say that our lizards had no difficulty in moving within the appropriately memorized clearing of residence. According to the most accredited views in this field, a brain structure comparable to the hippocampal portions of the brain of birds and mammals could be the place where spatial information would be processed and memorized to constitute the aforementioned cognitive map.

In evolutionary terms this opens up a further context, which can be summarised in two hypotheses:

- the different groups of vertebrates would have evolved their own systems and mechanisms of orientation, given their fundamental importance in everyday life;

- starting from reptiles, the selection of unitary mechanisms of orientation is admitted, which were then maintained evolutionarily in mammalian and avian descendants.

Another scientific challenge to be solved in the future!

- Natale E. Baldaccini, Federica Maffezzoli & Augusto Foà (11 Jul 2024): Initial orientation and homing performances in the lacertid lizard Podarcis siculus, Ethology Ecology & Evolution, DOI: 10.1080/03949370.2024.2343280

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/03949370.2024.2343280 ↩︎ - Direttiva Habitat https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CONSLEG:1992L0043:20070101:IT:PDF ↩︎

Credits

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic resources at University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers on national and international journals. He is active in the field of scientific education, and co-author of academic textbooks of Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, Comparative Anatomy.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa