The Englishman Alexander Parkes between 1861 and 1862, while developing his studies on cellulose nitrate, isolated and patented the first semi-synthetic plastic material: Xylonite. A few years later, the American Hyatt brothers, to replace the expensive and rare ivory in the production of billiard balls, patented the celluloid formula. Bakelite, Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Cellophane, Nylon (polyamide), Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), Formica (melamine-formaldehyde) were then patented and came onto the market. These materials replaced natural ones in just a few fields of application.

It was in 1954 that Giulio Natta, while completing his studies on ethylene polymerization catalysts, created isotactic polypropylene, which would earn him, in 1963, the Nobel Prize together with the German Karl Ziegler, who had isolated polyethylene the previous year. Polypropylene would be marketed from 1957 under the name Moplen and would revolutionize homes all over the world, entering the Italian mythology of the “economic boom”, aided by television that would bring it into Italian homes through advertising.

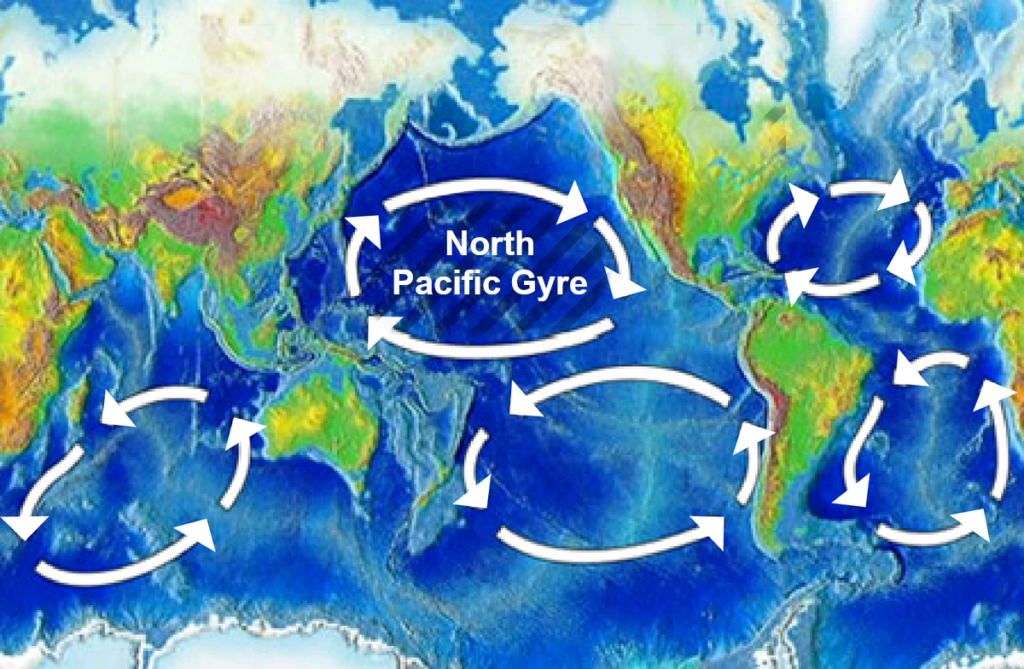

The low production costs, the great resilience and lightness of Polypropylene and other types of plastic materials that preceded it, have found a great variety of uses causing an acceleration in the development of thousands of new products. But products synthesized by man cannot enter the natural cycles of matter, so only after twenty years, in 1977, it is said that Captain Charles Moore, returning from an ocean race, encountered an expanse of plastic so large that it took him seven days to cross it: the Pacific Trash Vortex. In 1988, it was the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) of the United States that documented its existence to the world and renamed it. The island, which remains the largest of all those documented subsequently, was born as a consequence of the surface currents of the Pacific that, moving in a clockwise direction, create a spiral with an area of “still water” at its center. Our Mediterranean, classified as the sixth major area for plastic pollution on the planet, despite not being characterized by large currents, has its recently discovered plastic island: it forms cyclically between the island of Elba and Corsica and extends for kilometers.

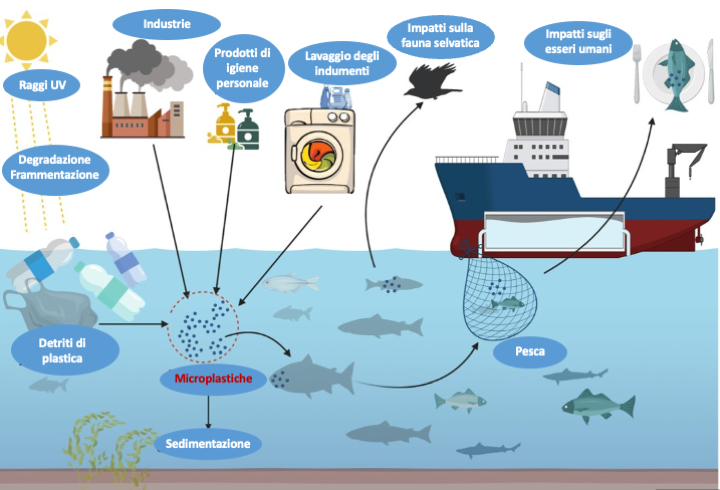

Since the 1980s we have begun to understand the extent of the problem we had created: ultra-resistant polymers do not exist in nature and nature does not know how to decompose them; however, we have continued to produce them, use them and multiply objects built with these “eternal” materials. But if they cannot be reabsorbed by the environment they can be degraded by ultraviolet rays, wind, waves, some types of microorganisms and temperature changes, breaking into increasingly smaller fragments, microplastics, which are then easily transported around the world and end up polluting even the most remote corners of the planet. Microplastics are divided into two main categories:

Primary microplastics: Plastic particles that are specifically designed to be small, such as plastic microbeads used in personal care products like exfoliants and facial cleansers.

Secondary microplastics: Particles that form from larger plastic items due to physical and chemical deterioration from exposure to environmental elements. A plastic bottle that degrades in the sea will give rise to secondary microplastics.

The continuous breaking down of microplastics generates nanoplastics, particles with a size between 0.001 and 0.1 µm (that is, between 0.000001 and 0.0001 millimeters). As demonstrated by a study published in Environmental Research, they have also reached the Poles, and for much longer than we think.

The study, coordinated by Dušan Materić, of the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research in Utrecht, the Netherlands, led him and his team to analyze ice cores taken in Antarctica and Greenland. All samples turned out to be rich in nanoplastics, half of which (for both the Arctic and Antarctic) came from plastic bags and purses. Among other sources of pollutants, it is worth noting that about a quarter of the nanoplastics found in Greenland come from tires, which are not represented in the Antarctic samples. But above all, it is worth noting that nanoplastics were found in the Greenland cores up to 14 meters deep.

What does this mean? When studying a “vertical” sample of ice, going deep also means going back in time, and finding nanoplastics at 14 meters indicates that these substances have been present in the area since at least 1965. This in turn means that nanoplastics are not a “new” pollutant, as previously thought, but one whose existence we ignored until recently.

Larger microplastics have been found in areas with high levels of untreated wastewater, such as off the coasts of Greece and Turkey. Macroplastics are abundant in areas with significant river inputs, such as the coasts of Algeria, Albania and Turkey, and near metropolitan cities and the highly populated coasts of Spain, France and Italy.

A 2021 study, published in Nature Sustainability and funded by BBVA, has drawn up a ranking of the ten objects that most pollute the oceans. The study highlights how most plastic waste comes from take-out food:

plastic bags 14.1%

plastic bottles 11.9%

food containers and wrappers 9.4%

synthetic fabrics 7.9%

fishing materials 7.6%

plastic caps 6.1%

industrial packaging 3.4%

glass bottles 3.4%

cans 3.2%

There is still much uncertainty about the real known effects on human and animal health. Of course, we know that they can be a problem for marine organisms, as the ingestion of these particles can cause physical damage, obstruction of the digestive system and the potential transfer of toxic substances along the food chain. UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) itself underlines how difficult it is to demonstrate the effects of ingestion of microplastics: for example, it has been observed that these particles can close the intestinal wall of mussels and oysters, inducing a reaction in their tissues.

On a different scale, North Atlantic fin whales, which feed on small invertebrates by filtering huge volumes of seawater, could see their feeding filter systems reduced. While these microparticles pose risks to both aquatic ecosystems and drinking water supplies by contaminating water, what is more concerning is the possibility that they could accumulate in the tissues of organisms, including ourselves, reaching increasingly higher concentrations as we move up the food chain.

Furthermore, many types of plastic can absorb a wide range of contaminants, such as pesticides or polychlorinated biphenols (PCBs), which can disrupt the endocrine system or lead to genetic changes or cancer.

A study led by Professor Dick Vethaak of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam analyzed blood samples from 22 anonymous, adult, non-pathological donors and found plastic residues in 17 of them. Half contained PET plastic, the type used in beverage bottles, while a third contained polystyrene, the material used in plastic bags. Previous work by the same medical team had shown that microplastics were 10 times higher in the feces of children than in adults. Children fed products contained in plastic objects swallow millions of microplastic particles a day.

While their health impact is currently unknown, this discovery demonstrates that plastic particles can travel through the human body, settling in organs.

An Italian research team led by scientists from the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli and coordinated by Professor Raffaele Marfella, who worked closely with colleagues from numerous Italian and European institutes, discovered microplastics and nanoplastics in fatty plaques in arteries (atheromas) and determined the association with a higher risk of death. The details of the research “Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Atheromas and Cardiovascular Events” were published in the prestigious scientific journal The New England Journal of Medicine.

At this point we ask ourselves: what animal, finding itself in difficulty with a specific situation, insists on repeating it? Answer: Homo sapiens sapiens! Twice sapiens! We prefer to suffocate the Planet that generated it in plastic, rather than stop producing it. Oh well!

Absurd, right? So let’s ask ourselves another question: what do I do to eliminate plastic from my life? Recycling? It is clear that this is not enough. In a world where the market decides, the decision is up to consumers: if no one buys plastic objects, especially disposable ones, they will no longer be produced. Elementary, my dear Watson!

We also point out the article:

https://www.earthgardeners.it/2017/10/12/earthgardening-plastica-e-mare-per-esempio/

Author: Anna Lacci is a scientific popularizer and expert in environmental education and sustainability and in territory teaching. She is the author of documentaries and naturalistic books, notebooks and interdisciplinary teaching aids, and multimedia information materials.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa