«The mind» argues Vallortigara «is not a tabula rasa. Learning from experience is possible only if the nervous system initially has a structure that favours it».

«When we reason about the origin of knowledge, it is difficult to get rid of the apparently decisive argument in favor of empiricism, according to which it would be impossible, even in the best controlled conditions, to be certain that an organism has been deprived of any kind of experience. Very true. But the point is not to demonstrate that some glimmer of knowledge is present in the absence of any experience, but rather to demonstrate that a certain specific experience is necessary for that glimmer of knowledge to reveal itself».

Thus Giorgio Vallortigara, Full Professor of neuroscience and deputy director of the Center for Mind/Brain Sciences at the University of Trento and Adjunct Professor at the School of Biological, Biomedical and Molecular Sciences at the University of New England, in Australia; author of over 170 scientific articles in international journals and popular book andone of the most internationally renowned Italian scientists for his investigations into the neural mechanisms of animal cognition, redraws the boundary between biology and the world of metaphysical speculation. An example of this is Kant’s Chick, a fascinating essay on imprinting and the origin of knowledge featuring chicks, the subject of experimental studies conducted for almost thirty years in parallel with those on human newborns.

In twenty-nine short and attractive and easy to read chapters,this new book by Vallortigara (published two years ago in English by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and now translated into Italian by the author himself, with revisions and expansions of the text) deals with imprinting and the origin of knowledge, through the documented presentation of his own and others’ experiments. One of the distinctive merits of the text is the apparatus of drawings by the artist Claudia Losi, who here too unleashes her passion for nature and life, which runs through all her work. (Morelli, 2023)

Specifically, Vallortigara uses the experimental paradigm of imprinting in birds (the one that made Konrad Lorenz, one of the fathers of ethology, famous) to reveal with incredible effectiveness, the existence of a real “predisposition” towards adaptive behaviors, that is, functional to the survival of the organism, in response to animate (other living beings) and inanimate (objects) environmental stimuli. Just like what happens in the imprinting of chickens in which the first organism (which may even be an object) that interacts with the chick is identified as the parent. (Peretto, 2023)

Publisher: Adelphi, 2023 | Pages:162, Paperback | EAN: 9788845938146

Today we clearly know that genes and environment cooperate to organize neural circuits and therefore that our behaviors are the result of this interaction. However, some aspects of this interaction remain rather obscure, such as the relative weight of genes and environment in shaping the neural circuits that control so-called “salient” behaviors that are important for survival. From this point of view, the essay is truly revealing. It illustrates with nume”rous examples that in chicks it is possible to obtain responses to specific environmental stimuli, thanks to the existence of a neural substrate whose organization already presents a “predisposition” towards these same stimuli, that is, independently of previous experiences. Therefore, there would be “innate” abilities that represent the cognitive baggage necessary for chickens to survive. This innatism, although necessary, should not be considered completely exhaustive, but rather the starting point for the individual to operate in the environment correctly and, probably, also the substrate on which experience will act, optimizing the interaction with the environment. (Peretto, 2023)

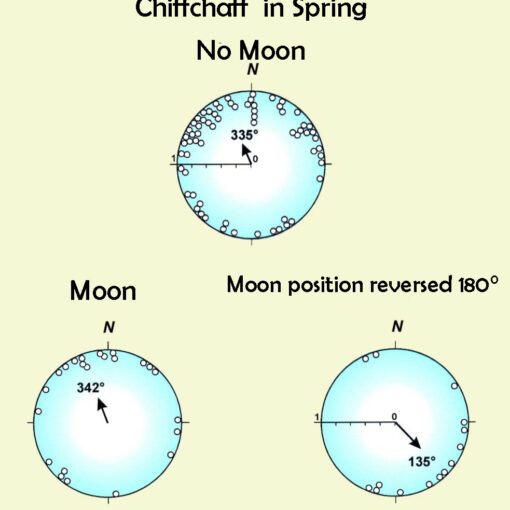

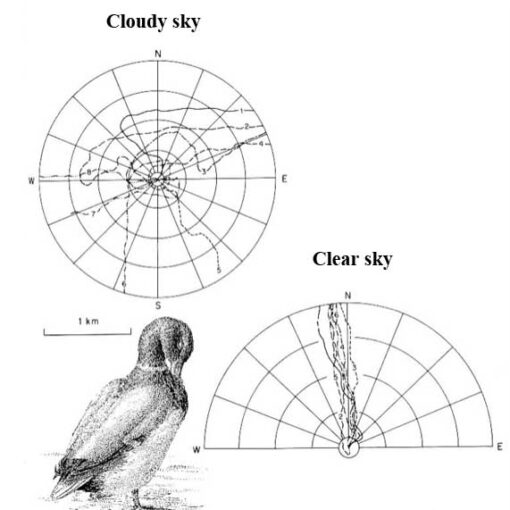

There is much evidence for the idea that we have innate predispositions that facilitate the imprinting process, put forward by Vallortigara to support his hypothesis. In the behavior of chicks, for example, the preference for the visual aspect of the head and neck region of a hen does not seem to depend on any particular visual experience or on learning through exposure to such stimuli. The brain’s equipment for recognizing faces is already present from birth. All this also occurs despite the phylogenetic distance and also concerns the young of the human species, despite the common ancestor between birds and mammals dating back almost three hundred million years. “The young of both species are attracted to schematic faces in which three spots arranged in the shape of an inverted triangle can be recognized within a circle“, writes the author referring to two brilliant studies conducted in his laboratory, together with O. R. Rosa-Salva, L. Regolin, T. Farroni and M. H. Johnson. The relationship with space and movement also appears to be common to animals characterized by a single plane of symmetry that first appeared five hundred and fifty million years ago. Starting from what an unforgotten scholar like Giorgio Raimondo Cardona called “the six sides of the world”, we do not only have an above and a below, but also a front and a back and a right and a left. Just like chicks, even small women and men show a preference for movement linked to the direction of the antero-posterior axis. It seems that we have, in short, an innate guide for learning or, as Lorenz called it, an “innate elementary school teacher.” Having such an innate guide certainly does not exempt the small chick or the small Homo sapiens from having to learn its vital tasks: it only facilitates learning. Just as it facilitates the predisposition to recognize the presence of other living beings in the environment: it is as if we had life detectors capable of recognizing highly specific signals, similar to the devices used during natural disasters. “In this deep memory”, concludes Vallortigara, “which has the long times of natural history and not the short ones of individual development, lies the origin of information, of the wisdom that organisms possess as basic equipment”. (Morelli, 2023)

A question finally emerges: when does life begin? If by innate we mean before birth, that is one thing, but if we consider what happens in the womb or in the egg, it becomes relevant to consider the relationship between phylogeny and ontogeny in learning and it seems important to explore whether, also based on studies on human fetuses in the womb, we cannot speak of learning before birth and, for chicks, before hatching, or whether there are, in this field, species-specific differences in vertebrates, between mammals and oviparous animals. For now, following the convincing and validated analyses of Giorgio Vallortigara and the traces of his chick, we can share that children and chicks are born and become such. (Morelli, 2023)

Author: Anna Lacci is a scientific popularizer and expert in environmental education and sustainability and in territory teaching. She is the author of documentaries and naturalistic books, notebooks and interdisciplinary teaching aids, and multimedia information materials.

Translation by Maria Antonietta Sessa