Many generations of zoologists, like mine, have been educated on texts of Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrates that reported reduced olfactory abilities for birds. They were considered microsmatic, a species in which the sense of smell had a small role in their behaviour, including searching for food. But that is not exactly how things are, even if it was a young Charles Darwin who contributed to creating such a belief, with an experiment on South American vultures that were unable to find pieces of meat hidden from view. But it was 1834…

The anatomical substrate

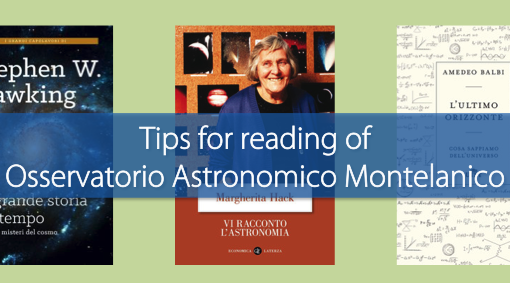

In birds, the nasal cavities follow the reptilian design, consisting of three successive chambers (Image 1), with varying complexities due to the conchae (turbinate bones). The olfactory epithelium covers the most caudal chamber, and its receptor cells share similar anatomical features with those of other vertebrates. The nasal chambers are often arranged to direct inhaled air toward the epithelium, and the number of conchae can vary, with kiwis having up to five.

b) Section of the nasal cavity of the kiwi.

c) Cross-section of the beak of a fulmar (Tubinari) showing the turbinate structure of the olfactory tubercle. From Portmann 1961. Image 1 – a)

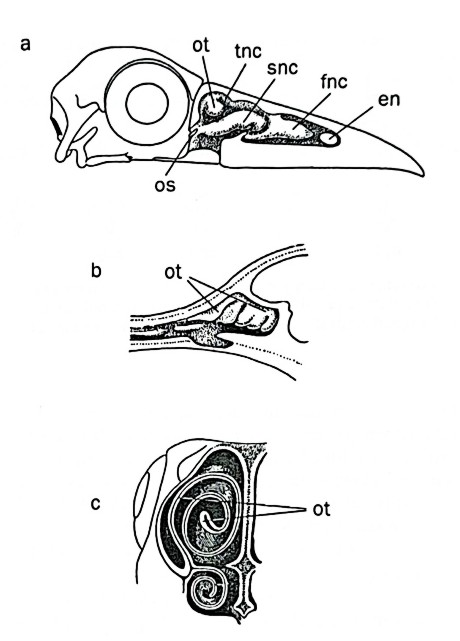

The epithelial receptor cells connect centrally with the mitral cells contained in the olfactory bulb, via the nerve of the same name (Image 2). The bulb is located in front of the telencephalic hemispheres and consists of two parts that are not always the same size, largely fused. Its size is correlated with the extension of the olfactory epithelium. From the bulb, in turn, the olfactory radiation starts towards surprisingly large parts of the telencephalon and the diencephalon (hypothalamus), that is, with areas that allow more opportunities for interaction with other sensory systems or for the coordination of complex behaviors, from motor control to imprinting. Of particular functional importance is also the anterior olfactory commissure, which allows the exchange of olfactory information between the two hemispheres.

The functional aspects

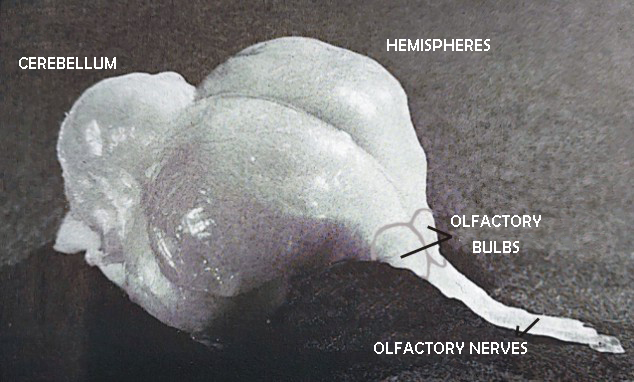

But how is a species considered macro or microsmatic from an anatomical point of view? It is done based on the dimensional ratio between the maximum diameter of the largest olfactory bulb and that of the cerebral hemisphere located on the same side (ipsilateral).

In carnivorous mammals, the olfactory bulbs are typically large, especially when compared to the size of the brain, and are rightly considered macrosmatic. Whales, however, have very small, almost cryptic olfactory bulbs, making them anosmatic. Primates, on the other hand, have intermediate-sized olfactory bulbs, generally classified as microsmatic. However, referring to the “noses” involved in industrial perfumery as microsmatic seems somewhat outdated!

Birds, like mammals, exhibit a complex range of diversity, vividly illustrated in Image 3, which presents data on the bulb/encephalon ratio across various species. The kiwi boasts the highest values for this parameter, with its large, reptilian-like bulbs, closely followed by several procellariform species, including albatrosses, storm petrels, and shearwaters (refer to Image 4). In contrast, passerines such as starlings have very small bulbs, a trait also observed in non-passerines such as doves and swifts.

Image 3 shows a significant decrease from procellariforms to passerines, indicating a trend towards more recently evolved species. However, this pattern is not solely a systematic correlation. The size of the olfactory bulbs also correlates with habitat, diet, and nesting patterns, as well as nocturnal or crepuscular habits. Species with these habits tend to have larger bulbs than diurnal ones, suggesting that a keen sense of smell may be a general adaptation to low light levels.

The size of the bulbs might not account for everything as they offer limited insight into the connections of the receptors they hold, their central projections, and the brain centers they engage to convey olfactory information. Just as visual acuity is not solely dependent on eyeball diameter, olfactory acuity operates independently of bulb size. When researchers began exploring these capabilities in the 1970s, they encountered numerous unexpected findings.

As previously noted, all birds exhibit extensive development of the bulbar olfactory pathways. It is equally surprising how they can discriminate odours and perceive solutions of odorous substances at very low concentrations, regardless of the size of their olfactory bulbs. A bird at rest, monitored electrocardiographically, will show an increase in heart rate when exposed to a current of air containing an odorous substance, with varying reaction intensities depending on the substance and its concentration.

In pigeons, the reaction threshold for menthol is 0.10 parts per million (ppm), while magpies react at 0.25 ppm to the same substance. In contrast, pigeons react to pentane at 16.45 ppm, whereas roosters respond at 1.58 ppm, highlighting different thresholds among species. Pigeons, in terms of reaction to changes in the concentration of inhaled substances, show abilities comparable to those of rats, which are macrosmatic with high olfactory acuity. Notably, birds, like Pavlov’s dogs, can be conditioned, to respond to odorous stimuli, illustrating how these can trigger complex behavioral systems.

Olfactory stimuli and behaviour

A fundamental principle of empirical research is to “ask nature the right questions.” Early attempts to assess the sense of smell in birds aimed to determine if vultures, known scavengers, located food by scent. These experiments were so unusual that they yielded no positive results. However, the researcher behind them was Audubon, a prominent American ornithologist of the nineteenth century, who strongly dismissed the idea of birds possessing a sense of smell. His influence was so significant that no one challenged his views, leading to the myth of birds being anosmatic.

The kiwi makes loud sniffing noises as it searches for food with its nostrils at the top of its beak. This allows it to locate small holes containing earthworms hidden under 12 cm of soil, distinguishing them from others that do not contain any. Equally remarkable is the ability of the procellariiforms: they are drawn to sponges soaked in cod liver oil thrown into the waves, ignoring those soaked only in seawater. We now believe they can locate shrimp schools by smell, as generations of whalers, navigators, and ocean fishermen have long suggested. Extensive experimental tests have also shown that shearwaters and storm petrels can find their nests through scent cues, at least during the final part of their long foraging flights, even when their nests on remote Antarctic islands are covered in snow.

The nose also plays an important role in the return of carrier pigeons to the dovecote, but I will share more about this on another occasion…

Author: N. Emilio Baldaccini. Former Professor of Ethology and Conservation of Zoocenotic Resources at the University of Pisa. Author of over 300 scientific papers in national and international journals. Actively involved in scientific education and co-author of academic textbooks on Ethology, General and Systematic Zoology, and Comparative Anatomy.

Translated by Maria Antonietta Sessa